What we write has a brief moment of life between its preliminary nothing and its ultimate destiny at the bottom of the cat tray. A piece of journalism is a bubble, floating in the air, perhaps to blow away unseen, perhaps to provoke a crow of delight: before it pops.

What we write in a hurry is read in a hurry and forgotten in a hurry. Our work, like certain adult, sexual forms of insect, has a life of only a few hours. Our only aim — our only possible aim — is to make them good and fertile hours. The only way to make them good is by sowing a seed in the reader’s mind. Like the athletes we write about, we must write as if the work we did were the most important thing in the history of the world; and do so in the sure and certain knowledge that it is nothing of the kind. Our lives depend on that contradiction. If we cannot master both halves of it, we are worth even less.

That is Simon Barnes, writing on the central contradiction in a sports journalist’s life. Sport is ephemeral; it provides joy — and sometimes, meaning — in the moment, and is forgotten in the moment. Around us, the world continues to teeter on its axis (shortly before I wrote this, while I was catching up with the news, I noticed that a stand-up comic is in jail for a joke someone thinks he might have cracked —it made me realise that we are living in a world where we can be imprisoned for thoughts someone else thinks we might have thought). And in the midst of this madness, we write of a sporting event as if the fate of the world depended on its outcome, as if humankind were holding its breath, waiting to see what we — the “writers” — make of it all. The more fools we — and yet, here I am, writing about events that are nearly a week old; its outcome known, its individual details largely forgotten.

That’s the thought that prompted this post: individual details. We all remember that moment when Josh Hazelwood went round the wicket, in the 97th over of play, with the field drawn tight to prevent singles and somehow eke out a null result. The moment when, to a ball angling in to his off stump from wide of the bowling crease, Rishabh Pant used his wrists like a painter to propel the ball through a narrow gap at mid off. We remember that moment when the ball raced off his bat, across the turf, and into the history books.

Pant is an original. As that 97th over began, Sanjay Manjrekar in the commentary box was calling the field, and speculating about what shot the batsman could play, into which area of the ground, to find a single. That is the pragmatic approach, the one we are all so used to. That approach is antithetical to Pant’s batting sensibility — the utilitarian approach is not for him. A week ago, in Sydney, when everyone was speculating about what it would take for India to pull off a draw, he came out looking for the win — and damn near pulled it off. If you could pick one Indian player who will walk a tightrope stretched across the Grand Canyon, chattering as he goes, it would be this guy.

He is always described as ”short-statured”, “stocky”. In actual fact, he is 1.7 meters (5 feet six inches) tall — 0.5 meters taller than Prithvi Shaw, 0.5 meters shorter than Virat Kohli. Appearances are deceptive — some cast long shadows, others not so much. JT Edson, an Englishman who made a fortune writing gunsmoke-shrouded Westerns, had as his central character one Dusty Fog, leader of the “Floating Outfit.” In every single book — and there are dozens featuring Fog — his first appearance in the story is to the accompaniment of a detailed description of his short stature and his nondescript looks. And then a fight breaks out; Fog pulls his two Colt Peacemakers out of the cross-draw holsters in a “flickering blur of movement”. And, every single time, Edson writes of how he suddenly grew in heft until he seemed to be the tallest man in the room.

The comparison is particularly apposite in a country that sets people up on pedestals only for the dubious pleasure of bringing them down. I intended to elaborate on this a little — but Cricinfo makes the effort needless, with this clip. Watch:

We saw what he did. In Sydney, when he almost pulled off an improbable heist. In Brisbane, where he audaciously, improbably, defied history and reputation. I wonder what it took for him to bat the way he did — to carry the burden of criticism, to internalise what the team needed from him, and yet to play the only way he knows to play, aware every time he swings his bat that he is one false shot away from another barrage of vicious criticism.

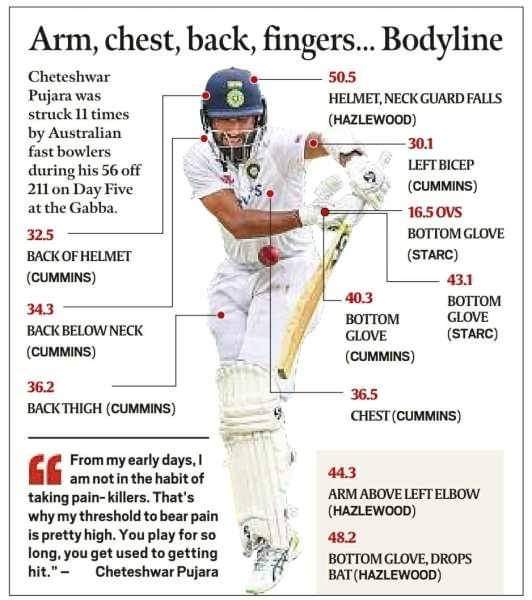

TIRED legs. I heard this a lot from the commentary team during the final session of that last day, which was the only session I could really watch. It made me think of commentary — written and oral. If, for instance, I had to write a report at the end of day four, I am fairly sure I’d have focussed on the difficulty of the task ahead of the Indian team. I’d have talked of the reasons no visiting team wins at the Gabba. About the widening cracks, and what that means for batsmen who cannot predict what will happen when a ball hits one of those fissures. I’d have talked of the attack they were facing — the nagging consistency of Hazelwood; the brilliant angles that Cummins conjures up; the turn and bounce Lyon gets; the unpredictability of Starc and his lethal quality when bowling to the tail.

I’m sure I wouldn’t have written that India would find it easy because Aussie legs were “tired”.

Still playing the game of ‘what if’, I wonder what it would have been like if Australia had gotten a wicket early in the opening session. Would their legs have been “tired”? That makes me think of the importance of the Gill-Pujara stand, during which in their contrasting ways, they not only soaked up 39 overs worth of intense pressure, a lot of it with a brand new ball, but also kept the board ticking, bleeding the bowlers and taking little chunks off the target.

Here’s the thing: The Aussie bowlers were only as good as the Indians allowed them to be.

Pujara’s amazing Horatius-on-the-bridge act has been justly celebrated; not as much has been written about Gill. A young man, in just his third Test, against one of the best bowling units in the world, facing a task history said was impossible, playing with complete unconcern and an uncanny ability to focus on just the one ball that is being bowled to him.

I’ve been impressed by the ease with which he plays off front foot and back; his assured judgment of line and length; his ability to pick the right stroke for each ball from a complete arsenal. But the moment I sat up and took notice was when, earlier in the series, he got out playing a shot and later, when asked about it, he said “I did not want to miss a chance to score.”

That is when I realised he was a serious talent, for the long term. It’s the nature of international cricket — a player will emerge and do well; oppositions will study him, look for chinks, try different strategies, and expose vulnerabilities. The neophyte, now under pressure, will be tested when things begin to go wrong; he will have to recalibrate his game, find new answers to fresh questions, and he will have to do all this under intense scrutiny. But as long as he has that attitude — that his job is to go out there and make runs — the rest will follow.

But, “tired legs”. And that made me think — the seeds of this win were first sown on the fifth day of the Sydney Test, when Ravi Ashwin — who couldn’t bend — and Hanuma Vihari — who couldn’t even walk — weathered over 42 overs to save the game. The three Aussie pacers bowled 74 overs between them in that innings (and a total of 136 overs in the match) as India resisted for 131 overs to save the game — a serious, and eventually futile, effort that would have left them drained in body and in spirit even before the Gabba Test began.

Still tracing the seeds of this win, I thought of the morning of day two at the Gabba. 274/5 Australia when play began — not a bad score, but nowhere near what the home team would have wanted after winning the toss and batting first. What struck me about the second morning was the Indian attitude in the field. You would expect to find in-out fields, and bowlers bowling restricting lines to prevent the batting side from piling up runs. Instead, India came out attacking. Two, sometimes three, slips; at least one catcher in the leg trap always, either at short square or leg slip. Often a silly mid on or a short midwicket, catching. Point and cover drawn taut inside the circle. Bowlers attacking both edges and the stumps. Bowling out the five remaining Australian wickets — with Siraj and Shardul relentless with their lines and lengths — was huge. In team sports, you can fall behind at times, and that is okay, it’s how sport works. The one thing you can NOT do is allow the opposition to get so far ahead that there is no chance of catching up, and that is what the Indians did so well on that second morning: they kept Australia within reach.

More seeds: The partnership between Sundar and Thakur. From 186/6 to 309/7, a resistance that lasted 32 overs and five deliveries and produced 136 runs between them. And not just dogged back to the wall resistance, either. Thakur defended his first ball; survived an appeal for LBW off his second, and then improbably, impossibly, hooked no less than Cummins for six over fine leg. From that point on, both Sundar and Thakur played almost like seasoned batsmen — cover driving fluidly, hooking and pulling to counter the short balls, rolling the strike over, putting on a display of batsmanship at its best and, in the process, accomplishing two key objectives: Keeping Australia’s lead down to manageable limits, and wearing down the home side’s pace troika.

By the time the Indian first innings ended, the Aussie quicks had bowled a further 74.4 overs on already tired legs.

I remember telling a friend, as the Australian second innings progressed with no batsman being able to capitalise on a start, with the Indians bowling with discipline and fielding with dogged determination, that I was willing to bet good money Rahane’s unbeaten record would remain intact. Here’s what I was looking at: Tim Paine’s reluctance to go for the kill. As the innings extended with no sign of the batsmen going all out to increase the lead, I realised what this Indian team had done: they had forced Australia to respect them with both ball and bat. The Aussie batsmen didn’t think India’s bowlers could be taken; the Aussie think tank wasn’t sure how many runs it was safe to set this batting lineup, despite the fact that it contained only two batsmen from the original lineup.

When a team gets into that frame of mind, you know that despite what history says, despite what the scorecard shows, it is the seeming underdogs who actually have the upper hand. Australia is used to visiting teams folding at the first sign of adversity; when they go up against a team that refuses to fold its tent and limp home, their tiredness is not just of the legs, but of the mind.

And one final seed: Rahane, coming out in the second innings at the fall of Gill and playing a 22-ball 24. It’s not the runs he scored, but in the signal he sent — India was not inclined, that innings said, to retreat into defence. They were in it to win it — the one message a fast bowling unit who, by then, had bowled 211 overs across three innings didn’t want to hear. And that message was reinforced when, at the fall of Rahane’s wicket, it was Pant — the batsman who in the previous game had come this close to pulling off an improbable heist — and not Agarwal who walked out.

It is this that made this India-Australia series special for me. Not just that India won; not even that India won with 9 of its first choice players unavailable by the end; but that India won not on the back of the stirring deeds of one or two superstars but thanks to a collective effort involving every single one of the 20 players who featured across the four Tests, AND the contributions of those who did not get to play.

That is why the magic moment, for me, was watching Kuldeep Yadav — a bowler who has won games for this team and now found himself a supernumerary even in an injury-decimated side — pause on the boundary line to pull on his India cap before racing out to congratulate Pant and Saini.

“For the strength of the wolf is the pack, and the strength of the pack is the wolf”.

For the entirety of three Tests, I did not for one single moment miss the “superstars” who missed out. Did you?

PostScript: While I was in Calicut for the last rites of my uncle, I was asked by Sruthijith, editor of Livemint, to write a piece on the Brisbane Test. I couldn’t write then, not in the frame of mind I was in. Sruthijith understood, and he told me he would wait till Sunday for a piece, which he could publish Monday, January 25.

That piece has been written and sent; I’ll update this with the link once it appears. This post is about a thought — thoughts — I didn’t have space for in that one.

PPS: Livemint editor Sruthijith had reached out as the game at Brisbane was winding down. Since I was in no shape to write at the time, he kindly gave me till Sunday noon to file. This is the piece (It is behind a paywall).

13 comments

0.5 meter shorter than Kohli!…… surely this is a typo.

Surely not. There is a point to be made there, about reality versus perception.

Your point well understood. We always perceived Pant to be shorter than 5’6″ to be honest. 🙂

However, 0.5 meters is actually over a foot and a half. I think what you meant to say was 2 inches or 5 cms, which is 0.05 meters. Kohli stands at 1.75m, doesn’t he.

Forgot to mention that I loved reading the piece!

Hi Prem, nothing personal but people do not perceive Pant to be shorter than Kohli by half a meter!

BTW I really enjoy your writing

Hey, no offense taken. The only thing I bar is abuse — disagreement is just fine; each of us processes things in different ways.

Brilliantly written as usual, Prem. I wish you’d write more… & much more often!

Thanks, Darshak. FWIW, there’s this: https://www.livemint.com/sports/cricket-news/revenge-of-the-lambs-at-the-gabbatoir-11611499668771.html

I think Darshak meant write more in front of the paywall 🙂 Prem, you are a magician with words, every single piece is brilliant.

For a celebrity writer like you, I am sure Livemint would actually mint money just through ads based on the traffic and still outside of the paywall 🙂

Thrilled to see a JT Edson reference 🙂 Haven’t heard of a lot of folks reading them. I cleaned out a used book store when I saw it in the US when I first moved. Awesome writing as usual.

Hahaha. There was a time when I read Edson, Zane Gray, Oliver Strange, Frederick Christian and such obsessively, despite the repetitive nature of the storytelling. Still have almost all those books.

I think Darshak meant write more in front of the paywall 🙂 Prem, you are a magician with words. Every single piece is brilliant. For a celebrity writer like you, I am sure Livemint would mint money through ads just based on the traffic and still outside of the paywall 🙂

It’s a bit complicated, Amit. Media houses, under financial pressure, are less willing to pay decent writers a fair wage. (It’s not like I went away or something, but it’s been years since anyone asked me to write). And to be fair to Livemint, the original intention was to keep this story outside the paywall, but something went wrong in the works. And, still on the fairness principle, they are very good to work with — they accommodated my personal issues, were willing to wait till I was in a place where I could focus and write, and gave me the space I needed without asking for cuts — a big thing for a business-oriented paper to do.

Comments are closed.